Introduction

The Llangollen Canal and Pontcysyllte Aqueduct brought new opportunities and increased access to markets. Iron was worked at several furnaces and forges while coal was mined in pits at Cefn, Plas Kynaston and Dolydd.

Retail businesses flourished as people from surrounding villages came to buy food, clothing and hardware such as J Thomas Tinsmith who supplied water and ‘snappin’ tins for the colliers. Growing numbers of chapels and pubs served the spiritual and social needs of the village.

Graesser’s chemical works was established to extract paraffin oil and wax from the local shale and went on to become the world’s leading producer of phenol.

Click on any Point of Interest marker to view the description

1. Plas Kynaston

Plas Kynaston was built by the Kynaston family who owned substantial lands in the area of Cefn Mawr and Trevor from the early years of the 17th century.

Humphry Kynaston’s only child, Mary, married William Mostyn in 1711. When their son also succeeded to the estate of William Owen, he adopted the surname Mostyn-Owen. William Mostyn-Owen was one of the principal promoters of the canal linking the rivers Severn and Dee via Ruabon.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

William Mostyn-Owen died heavily in debt in 1795. His son of the same name continued his father’s active involvement with the canal and tried to pay off the debts. By then industry was developing in the area. Coal mines were dug and William Hazledine leased land for his foundry which supplied the ironwork for Pontcysyllte Aqueduct. The entire Plas Kynaston estate was sold between 1813 and 1819.

Plas Kynaston branch canal allowed easy access for goods to and from town past the foundry to Trevor Basin and by the 1870s the estate also had a colliery, chemical factory and a pottery.

After World War 2 Plas Kynaston was used as a school and a public library until a new library was built next to it in the 1970s. The empty hall was boarded up and after a few years it was placed on the Buildings at Risk Register. Fortunately it has been restored and turned into flats.

© Heather Williams

1879 OS map © Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

2. Cefn Kynaston, Hill Street

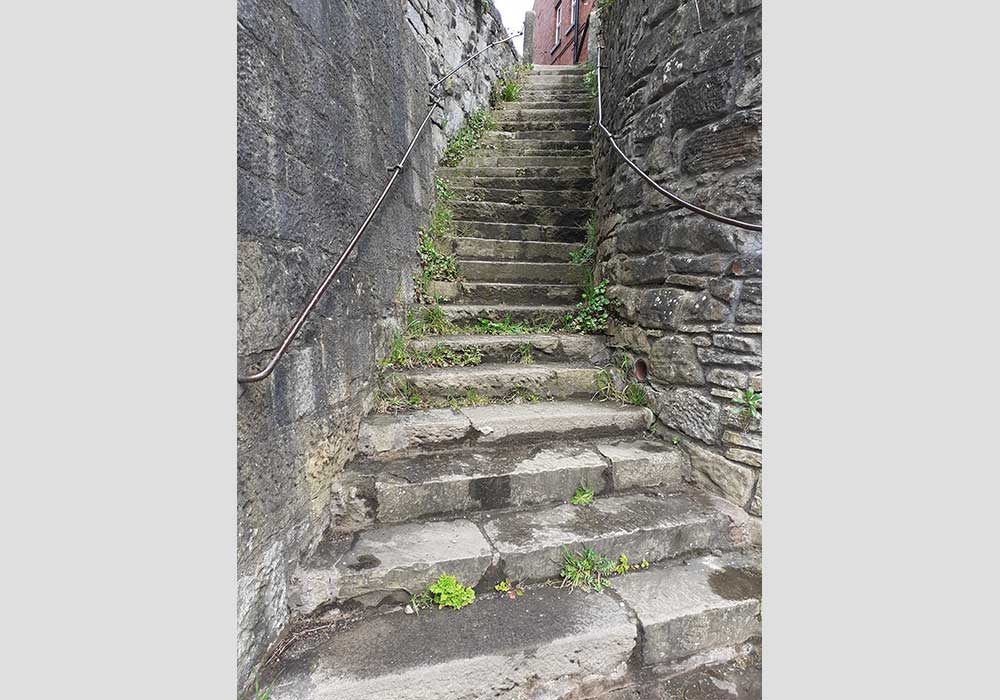

Cefn Kynaston is a beautiful sandstone house built in the early 1800s. It was the spacious residence of local doctors from 1897 until the 1960s and the steps behind the house that lead up to Crane Street are still called the Doctor’s Steps.

© Heather Williams

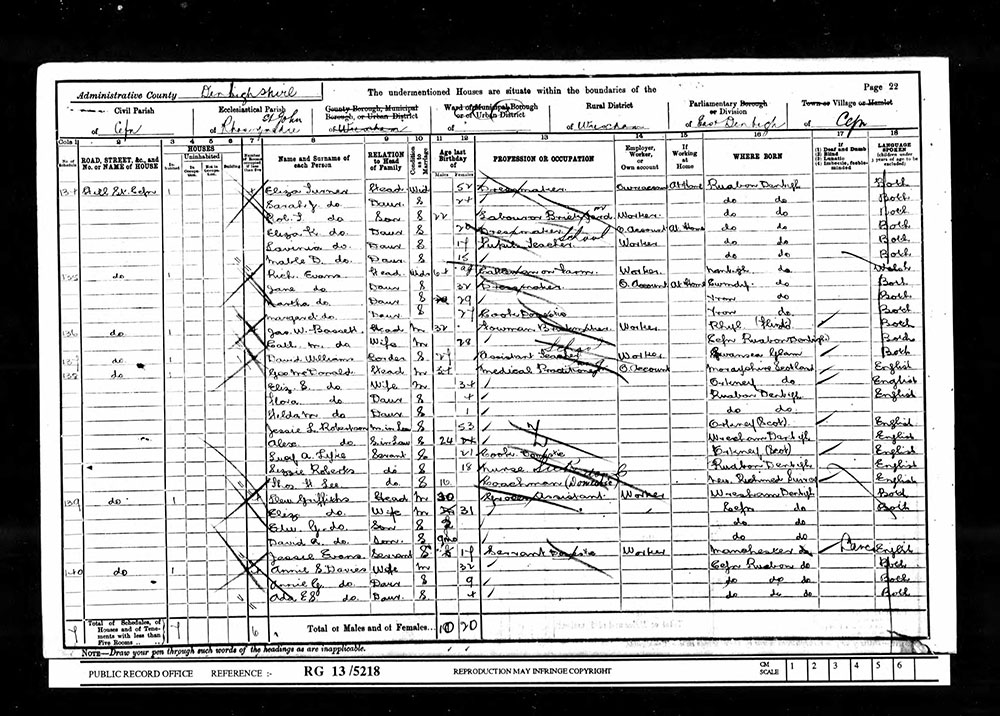

In 1901 Dr George MacDonald, who came from Morayshire in Scotland, was living here with his wife, two young daughters, his mother and sister in law together with a cook, nurse and coachman. By 1911 his in-laws had departed but he had a son. He still had a cook and housemaid but no longer needed a coachman.

© Heather Williams

1901 Census © The National Archive Crown Copyright 1901

3. Crane Street

Crane Street is named after the crane that operated here in the 1800s, transferring loads between two tramroad systems. This enabled goods from Cefn Mawr to be taken along the Ruabon Brook Railway to the Plas Kynaston iron foundry and then on to Trevor Basin.

Ruabon Brook Railway opened in 1805 and was cleverly engineered as it descended consistently with a slope of about 1 in 100, just right for the horses to be able to pull the same number of laden wagons down to Trevor Basin as empty wagons back up from the wharf.

Crane Street and Well Street were the main shopping areas of town, packed with grocers, hardware and other shops supplying all the needs of the town and surrounding villages.

One of the most elaborate and richly detailed buildings is Maypole at No 5. Maypole was a national chain of butter and margarine shops that started in Birmingham in the late 1800s and grew to 889 branches by 1918. Local specialists restored the cast-iron fascia, signage and the beautiful mosaic entrance in 2010.

Opposite is Craig Roberts, a traditional butcher’s shop, which has changed little since the late 1880s. There are four mosaics dating back to the late 1880s made from tiles manufactured at the former J. C. Edwards tile works in Ruabon; one of a ram, one of a pig and two depicting bulls.

© Heather Williams

© Heather Williams

4. Holly Bush Inn, Well Street

The Holly Bush Inn was built at the same time as Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, probably using stone rubble produced during the construction of the Aqueduct as only the best and hardest wearing heart stone could be used for that and other large constructions such as the Cefn Viaduct.

If the original plans to extend the canal to Cefn Mawr had come to fruition the Holly Bush would have been on the canal side!

Hollybush after renovations © Heather Williams

The Holly Bush was extended in 1830 and again by the 1870s as the town grew and prospered.

In 2012 the brewery decided to sell off the pub. At that time the roof was in poor condition with many leaks, loose and missing slates. Since then the whole of the building has been sympathetically repaired and restored, including the original vaulted beer cellar that has been renovated so once again people can enjoy a warm welcome and good beer at the Holly Bush!

Hollybush in 2010 before renovations © Crown copyright: RCAHMW

5. George Edwards Hall & Cefn Mawr and District Museum, Well Street

The George Edwards Hall was built in 1911 in memory of George Edwards, the brother of J. C. Edwards, the great brick and terracotta works owner. It was built with bricks from their works and was originally planned to be a theatre but struggled financially so in 1919 it became Cefn Mawr’s first cinema, ‘Kinema’ in the era of silent films and piano accompaniment.

By 1944 it had been re-named the People’s Cinema but closed in the 1950s and was once again used for concerts and other performances. The Hall is now run by the Cefn Community Council.

At the rear of George Edwards Hall is Cefn Mawr Museum, run by enthusiastic and dedicated volunteers. Opened in 2014 it celebrates the history and people in Cefn Mawr and the surrounding communities of Trevor, Acrefair, Pen y Bryn, Froncysyllte, Rhosymedre and Newbridge.

The Museum is packed with objects, photographs and documents that have been loaned or donated by local people and is divided into various themes including the canal and River Dee, village life, industry, transport, sport, churches and chapels, schools, art and music.

Two popular objects are a coracle that was used for fishing for salmon on the river and an original nut and bolt from Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

The Museum is open Monday, Wednesday and Friday mornings.

© Cefn Mawr Museum

© Cefn Mawr Museum

© Cefn Mawr Museum

6. Well Street

The tall buildings in Well Street mainly date from the late 1800s or early 1900s and represent a time of economic growth and prosperity in Cefn Mawr. There is a mixture of local sandstone and smooth red Ruabon brick, with some rich decoration on many of the buildings. There are also some yellow coloured buildings that are early examples of J. C. Edwards’ bricks.

No 31 Well Street is constructed with yellow bricks and was formerly two properties. Edward Davies lived here with his family in the late 1880s and you can still see the painted sign ‘E. Davies Stafford House’ with a 1869 date stone. He was a local man and sold musical instruments during the 1880s. By 1891 he was a grocer and earthenware dealer, with both his wife Emma and one of his sons, Edward, age 23, assisting him in the shop. Edward died soon afterwards and his son took over the shop selling crockery.

Numbers 32 and 33 Well Street are a pair of red brick semi-detached shops with living accommodation above. Number 33 has been restored with the early original shop signage above the first floor window showing it was the shop of ‘W. H. Morris, Complete House Furnisher established 1855.’ The sign probably dates from the 1940s as an early telephone number was also discovered.

Opposite are Paris House, Deva House and Central Buildings, some of the most impressive in the centre of Cefn Mawr and excellent examples of the diversity of local building materials and products being produced at the beginning of the 1900s. The rich terracotta detail including friezes, moulding round the windows and decorative motifs shows the skill of the local craftsmanship at the time.

© Heather Williams

© Heather Williams

7. Ebenezer Chapel

The early English Baptists in Cefn Mawr met in two small cottages on Well Street. In 1862 they moved into a building vacated by the Methodists and within a few months there were 136 attending the Sunday School.

© Heather Williams

They needed a larger building and the architect and builder Robert Jones of Belle Vue, Newbridge was appointed. He designed the massive sandstone Ebenezer English Baptist Chapel in the Gothic style, with a towering double gable frontage.

The chapel opened in 1873 and a new pastor was appointed. Prior to that they shared the pastor of the Welsh Baptist Tabernacl which was also on Well Street.

High moral standards were expected of the congregation and in 1888 additional rules were issued. Members caught frequenting public houses would be disciplined together with anyone caught going to the theatre or watching football contrary to the development of spiritual life.

The chapel was extended in 1899 reflecting the growth in the number of the Baptists who worshipped in the area. One of the stones to commemorate the occasion was laid by Mrs Jones, the widow of the original architect. In 1903 32 members withdrew from the church as they disagreed with the ‘instrumental arrangements’ and formed the new Bethel Baptist chapel. However, with the declining numbers attending the chapel it had closed by the late 1900s.

Major refurbishment of the building took place in 2008 when it was converted into a business centre with a café, gallery, studio and offices. One of the most striking features of this modernisation was the extension of the chapel at the front with a glass extension facing onto Cefn Square. As well as the original stained glass windows, inside the refurbished building it featured some new stained glass windows.

Sadly the building closed in 2013 but the local community hope to see the Ebenezer Chapel open its doors again.

© Heather Williams

© Heather Williams

8. Sandstone quarries (private)

The Cefn y Fedw sandstone quarries have been quarried since medieval times. The stone is a pale yellow when it is first cut but it weathers to a rich golden colour after a few years. Cefn Stone is hard-wearing but can be cut precisely to make a perfect fit between every block.

It was used for local churches, such as St Giles in Wrexham, famous buildings such as the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and was also an ideal stone for the construction of Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

© Heather Williams

Listen to…

…the sound of a quarryman tapping the rock

There were several quarries on the ‘big ridge’, which gives the village its Welsh name of Cefn Mawr. Sandstone was hand-worked from the quarry faces and old chisel marks can be seen on some of the stone in the old quarries.

Cefn sandstone is still used for new buildings and renovation work including the Aqueduct and the Holly Bush Inn.

© Andrew Deathe

© Andrew Deathe

9. High Street

The High Street runs on the big ridge and overlooks the area once occupied by Plas Kynaston Pottery and the Plas Kynaston Chemical Works.

Small cottages huddled around the quarry connected by a labyrinth of pathways, steps and stone walls. Much of this early housing was destroyed in the 1960s and 110 High Street is the only remaining example of an early worker’s cottage, now painted white with a slate roof.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

Many houses in Cefn Mawr take advantage of the steep slope and have more storeys at the rear. 110 High Street appears to be single storey but is actually two storeys.

Many of the ‘one up one down’ cottages were built by employers for their skilled workers. 118 and 120 High Street have date stones bearing initials. 88 High Street was built for a quarry owner but later became the Grosvenor Arms, one of many inns in the village.

By 1911 most people in Cefn Mawr were working as coal miners or work associated with the clay works rather than in the stone quarrying. One person who was working in the stone quarry was Edward Wright who was described as a delver, the old word for a worker in a stone a quarry. He and his wife Elizabeth were both born in Cefn Mawr. In 1901 he was living with two daughters and two sons at 120 High Street. By 1911 he had moved with his family to the red brick Lloyd Terrace further up the High Street. His two daughters were working by then, Barbara as a teacher and Edith Maud as a servant. His elder son, Dan, age 15, was working as a labourer in brick making and his other son, Lawrence, was still at school. In a family photograph taken at the beginning of World War 1 Dan is shown sitting proudly in his army uniform but sadly he was killed in France in 1918.

118-120 High Street © Heather Williams

110 High Street © Heather Williams

Lloyd Terrace © Heather Williams

Edward Wright Family c1914 © Courtesy of Stephen Adamson

10. Zion Chapel, Zion Street

Welsh Zion Baptist Chapel, or Seion a’r Tabernacl, was one of the earliest Welsh Baptist chapels built in Cefn Mawr in 1790s and was rebuilt four times as the congregation expanded.

The chapel was demolished in the 1970s and today only the peaceful burial ground remains with a stone from the church dated 1805 on the high wall beneath the burial ground.

The last time the chapel was rebuilt was in 1900 when George Richards, a consulting engineer, was presented with the trowel used during the laying of the foundation stones.

Evan Evans was an influential minister in the early days of the chapel. He began preaching in 1802 and three years later was ordained as a minister at Cefn Mawr. In the same year the local newspaper reported that the religious revival was growing in strength. ‘At Zion on Sunday morning the pastor immersed eleven, and five converts were made in the evening.’ Less than a month later the newspaper reported the number of new members had reached 82.

Evan Evans was concerned about the welfare of his congregation and helped the workers form trade unions, or combinations as they were called at that time. He helped to found Baptist chapels elsewhere in the area but on a visit to London to raise funds for the chapel he decided to become a milkman! He left the Zion Chapel and went to further the Baptist cause in London.

Elias Evans was his successor, a popular preacher, writer and organiser. He founded nine other churches in the immediate area and produced many publications, including the history of the Baptist denomination. He also tried to improve the social and moral welfare of the community which had been notorious for bull and bear baiting, cockfighting and street fights.

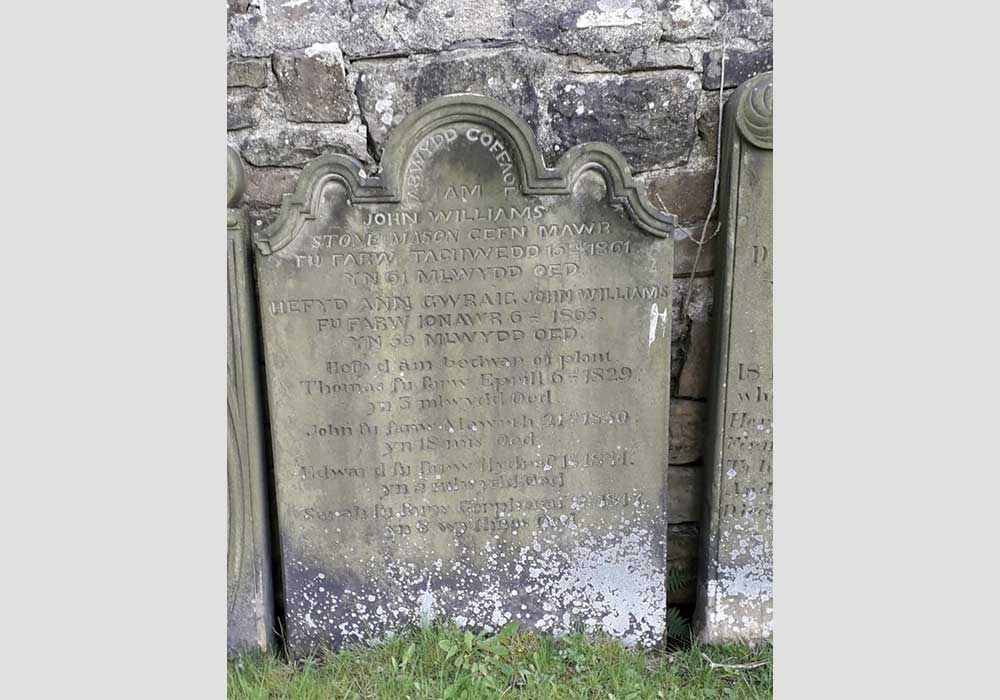

Gravestones inscribed in both Welsh and English in the burial grounds mark the lives of those who used to worship here including Thomas Richards, a lime merchant who died aged 45 in 1865 and John Williams, a stone mason, who died aged 61 in 1861.

The panoramic view from here has changed many times over the last 200 years with the rise and fall of the industries which have left their mark on the community.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

© Heather Williams

© Heather Williams